I have just finished reading David Didau’s recent posts on ‘progress’ versus ‘learning’ – The Problem With Progress – which you can find here, here and here. Taking as his starting point @kevbartle’s brilliant post on progress, @learningspy asks what is more important? Learning or progress? He goes on to explore various ways in which we can improve learning – even if comes at the expense of our ability to ‘demonstrate progress.’ It is a timely corrective and, as I read, I could almost feel the seismic vibrations of pedagogical plates shifting.

I have just finished reading David Didau’s recent posts on ‘progress’ versus ‘learning’ – The Problem With Progress – which you can find here, here and here. Taking as his starting point @kevbartle’s brilliant post on progress, @learningspy asks what is more important? Learning or progress? He goes on to explore various ways in which we can improve learning – even if comes at the expense of our ability to ‘demonstrate progress.’ It is a timely corrective and, as I read, I could almost feel the seismic vibrations of pedagogical plates shifting.

It is in the third of these posts that David refers to SOLO:

“I’m going a bit off-script here, but I’ve become increasingly convinced that SOLO taxonomy is most effectively used to plan learning outcomes; many of the tricks and gimmicks involved in explicitly teaching students about the taxonomy should, perhaps, be bypassed to concentrate on expanding students’ domain knowledge.

There, I’ve said it. I find SOLO incredibly valuable in helping me plan and organise a curriculum, but much of the time I was previously putting into teaching the taxonomy itself was based on the flawed belief that it would help students demonstrate progress. And make no mistake, it is great for getting students to demonstrate progress; but of what? If I accept that learning takes time and needs to build on a firm foundation of knowledge then there really isn’t any value in prompting students to show they’re able to more from multi-structural to extended abstract in a single lesson. All this demonstrates is the progress they’ve made in their ability to perform a particular task at a particular time. True extended abstract thinking develops over time. This is of course something we should plan for and it seems a sensible use of time within a spaced, interleaved curriculum that we should plan to take students on a journey from knowing very little, to knowing a lot, to being able to apply this knowledge in new and interesting ways.”

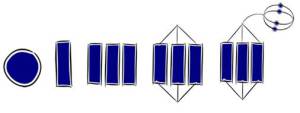

Cards on table: I love SOLO taxonomy. I was immediately drawn to its cool hieroglyphics and I found its simplicity refreshing. It had none of the confusing overlaps of Bloom’s taxonomy (identify appears in knowledge, comprehension & analysis) and it seemed to me, right from the get go, that this was potentially a very powerful teaching tool.

That isn’t to say that I didn’t have my concerns: I worried that it could turn out to be an artificial and ultimately unnecessary overlay on learning; I worried that what I took for beautiful simplicity was actually crude and formulaic; I worried that it would rule out other approaches to learning and teaching and I worried that it would not leave room for creativity. But once I tried it out in the classroom, I discovered that all of these anxieties had been misplaced. My pupils readily embraced it and it worked like a dream. However, as it was through the Learning Spy blog that I first discovered SOLO, alarm bells inevitably rang when I read about his new thinking on the subject.

Now, I recognize that David Didau has not consigned SOLO to the pedagogical scrap heap. He is simply questioning the value of devoting lesson time to ‘teaching’ the taxonomy with a view to using it to demonstrate ‘progress’. Indeed, he affirms the value of SOLO as a template for planning. However, my anxiety is that if we dispense with teaching the pupils the structures and terminology of SOLO, we reduce the power of this pedagogy and do our pupils a real disservice.

The ability to make progress visible is only the most superficial of the benefits that SOLO brings with it. The real power of this taxonomy lies in its ability to empower pupils in their own learning and to foster greater independence and resilience. There is something incredibly powerful in what I have come to think off as the forward momentum that is a defining aspect of this taxonomy and that is contained in the implied progress from prestructural to extended abstract. This is another of the key differences between Bloom’s and SOLO – the idea of progression between the levels is in inherent in SOLO and pupils grasp this quickly.

In my experience it takes next to no time to introduce SOLO. Following a simple card sorting exercise (see @totallywired77’s blog), the structures are embedded by means of their practical application in real time lessons. The pedagogy is never the point of the lesson – it is simply a scaffold for learning and it surprising how quickly they take ownership of the terminology. Once the penny has dropped and they understand the progression between the levels they actively want to move between the levels. I knew this to be true the first time a child approached me in class and said that he was working at a relational level, but needed additional support in moving to extended abstract (honest, it happened).

Having said all that, David Didau is undoubtedly right: the progress which pupils enact in moving from prestructural to extended abstract is not necessarily ‘real’ or lasting. Indeed, it is the irresistable forward momentum of SOLO that can lead teachers to devise lessons in which pupils cover all of the stages from prestructural to extended abstract in just an hour.The trick is to slow down and to resist the temptation to rush pupils through the levels. As with any other lesson in which peer and self is key, it is essential to ‘quality assure’ pupils’ assessments. Just because you’ve asked your pupils to stick their personalised post-it notes on the board under the SOLO symbol which reflects their current understanding, it does not follow that their assessment is reliable. An easy way to address this is to ask for a show of hands for each level and to challenge individuals to articulate why they think they are at such and such a level and then to ask pupils to reflect on this and reconsider where they would place themselves.

SOLO has given my pupils a sense of purpose and an independence in their learning which was often lacking. I don’t use it all the time – only when its appropriate. I am also aware that I have a great deal left to learn: I am yet to get to grips with SOLO as a tool for improving writing, but as a structure to support pupils in the close analysis of texts and the development of a personal response I have found it invaluable. This improvement in performance may, as @huntingenglish pointed out, be an example of the Hawthorne effect – the teacher’s enthusiasm for the new plus the pupils’ sense of being selected for something ‘special’ equals improvement in outcomes – but as time has gone on and SOLO has become a mainstay of my classroom repertoire, I’m inclined to think not. I have come to believe that there is something inherently empowering in this learning and teaching taxonomy. SOLO taxonomy does not get in the way of learning. It enhances learning by empowering pupils to take responsibility for their own progression.

So, here are just a few reasons to give SOLO a whirl: it is a brilliant way for teachers to plan lesson outcomes which moves from the superficial (quantitative) to the deep (qualitative); progress from one SOLO level to the next is implicit. Pupils get caught up in its forward momentum; it provides a common language for learning which helps teachers and students understand progress; it is fantastic for differentiation. See @lisajaneashes blog on how pupils can self-differentiate using SOLO;SOLO verbs and connectives make it very easy to integrate literacy objectives seamlessly into planning;it makes group work more purposeful, particular when work is focused on HOT maps;it is brilliant for peer and self assessment and feedback and feedforward.

Last but not least, members of the Maths department are quite put out when they see English teachers running around with armfuls of hexagons and this can only be a good thing!